Write to think, not just persuade

How “writing to think” became one of our core operating principles

👋 Hi, it's Greg and Taylor. Welcome to our newsletter on everything you wish your CEO told you about how to get ahead.

At Section we have an operating principle that sounds simple but drives everything we do: “We write to think.”

This means we write briefs for almost every project, large and small. Want to change our pricing? Write a brief. Thinking about a new hire? Brief. Considering a partnership? You know the drill.

Some people think this is overkill. I get it – if you're not used to writing, it can feel like we spend all our time documenting instead of executing. But at this point, we don't hire people who can't do this, because it's become essential to how we operate.

Here's why we do it, and how you can use briefs with your team (without making it feel like busy work).

- Taylor

Why briefs are mandatory at Section

Writing briefs creates value in ways that aren't immediately obvious:

It crystallizes your thinking. The act of writing something down forces you to work through gaps in your logic. You'll catch assumptions you didn't realize you were making before you start executing.

It forces rigor about the data and the “why.” When you have to write down your reasoning, you can't hand-wave through the important stuff. You have to actually know your numbers and be able to defend your logic. I often think I have a solid rationale for a project until I start writing it down. Then I think, “Wait… I don’t actually have data to support this” or even “... Why are we doing this again?”

It gives people something concrete to react to. Conversations in meetings often go in a circle. People misunderstand what each other are saying, and “agree” to things they’re actually misinterpreting. Briefs serve as a source of truth that stakeholders can comment on, edit, and improve. This is particularly essential in a remote company (which we are).

It becomes your source of truth. Six months later, when someone questions a decision, you can point back to the brief and say, “You agreed with this approach. What changed?” It eliminates the revisionist history that stalls projects and kills team morale.

The two types of briefs we use

Most of our briefs fall into two categories, and knowing which type you're writing helps determine what to focus on:

Type 1: The Alignment Brief.

The goal of this brief is to get everyone on the same page about the problem, the goal, and our approach. They usually start by laying out some background context – here’s the problem we’re addressing, what we’ve tried to date, and why we’re trying something new now.

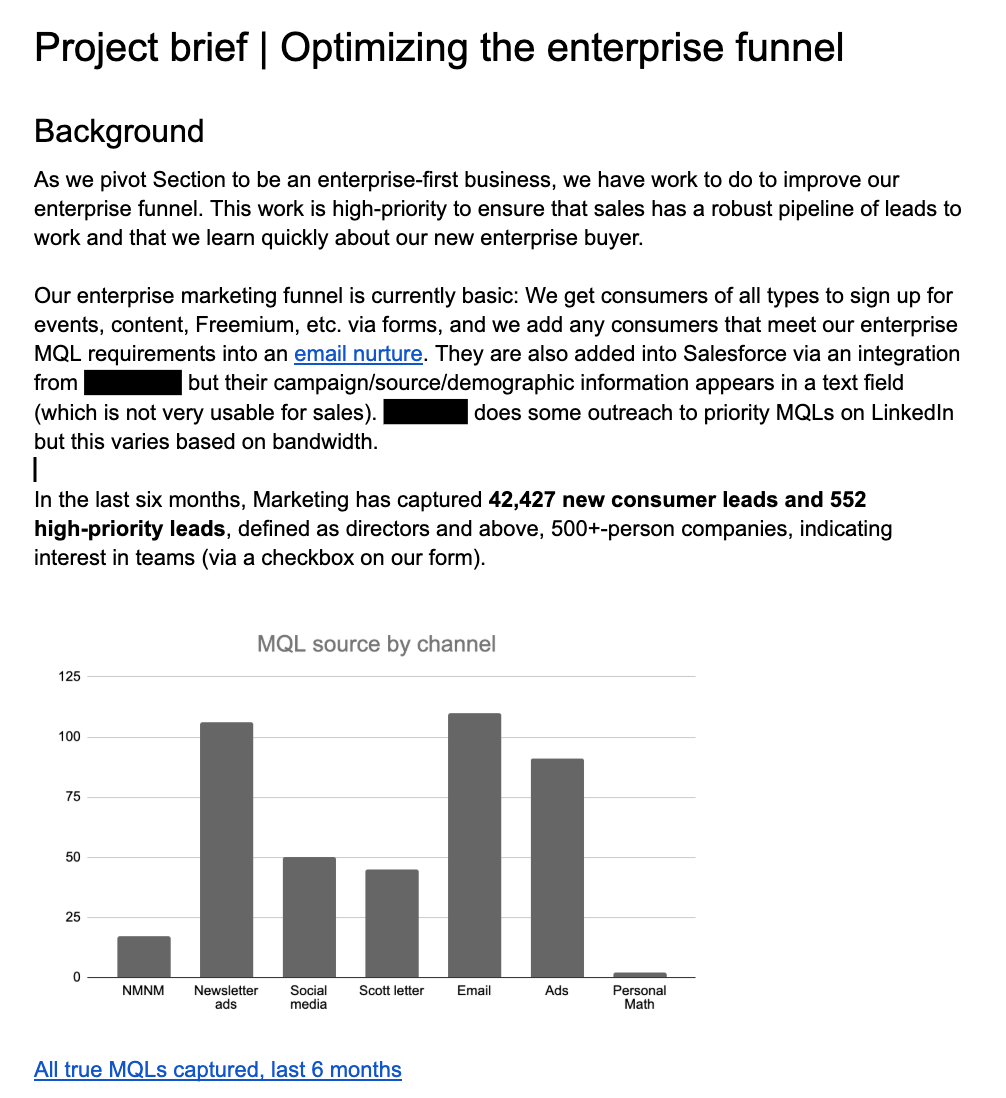

Here’s an example from earlier this year. As you can see, it clearly lays out the problem (the enterprise funnel is relatively basic) and the supporting data. If someone disagrees with the premise, they can add a comment saying, “This doesn’t make sense to me because of XYZ.”

From here, the brief should establish an approach to address the problem for people to weigh in on - in this case, a combination of lead sourcing, qualification, and nurture improvements to fix the funnel.

The goal of this type of brief isn’t to lay out every executional detail - it’s to make sure your team is aligned on the issue and your recommendation. For execution, we move to a second type of brief…

Type 2: The Execution Brief

You have a goal, and the brief explains how you'll accomplish it. These briefs must include milestones, dates, owners, budget, and tactical execution. Everyone already agrees on the destination – this brief maps the route.

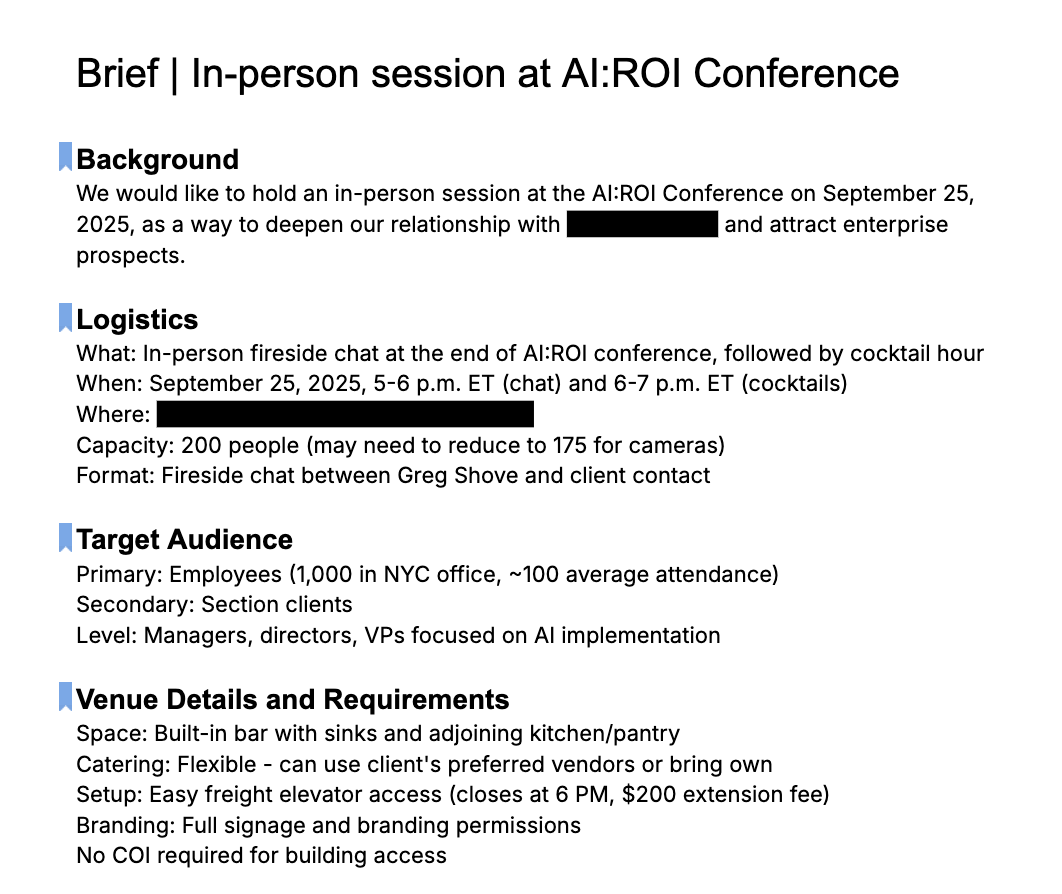

Here’s an example of this type. As you can see, the background section is much shorter because the goal has already been agreed-to (or is more straightforward). Instead, the majority of the brief is about logistics, audience, requirements, etc. – intended to organize the team on responsibilities and next steps.

Briefs aren’t busy work

We disagree that briefs are inherently busy work - but they can be, if you don’t use them properly. Here’s how to make them useful:

Remember that clarity is the point. Even if no one else reads your brief, the process of writing makes your thinking crisper.

Be clear about the brief's goal upfront. Briefs become busy work when you're unclear about what decision or alignment you're trying to achieve. Start with this mental framing: “After reading this, you should understand X and be able to decide Y.”

Make engagement easy. The brief works best when people engage with it. Make it easy for them by being specific about what kind of feedback you need and when you need it (not just “please read this and weigh in”). Include an executive summary - don’t make them wade through unnecessary background. Edit a LOT before you share - people are less likely to engage with 5 pages vs. 2.

Use the brief as a source of truth. Briefs are more likely to be busy work if they’re written and never returned to. Have the discipline to refer back to the brief, and reminders others to do the same.

Our advice

If you’re not a natural writer, briefs may feel more like a chore than a benefit.

Our advice: Break the brief into parts. You don’t have to write the perfect brief in one sitting (and actually, stepping away from it will help to clarify your thinking). Think of it in sections (Background, Analysis, Recommendation, Next Steps) and tackle one at a time.

And lean on AI for your weak spots. If you struggle with structure, ask ChatGPT to help organize your thoughts into a logical flow. If you struggle to cut back and summarize, ask GPT to create the exec summary or the feedback-ready version that’s 2 pages not 5.

Just don’t outsource the entire brief to AI – it will be extremely obvious to your team, decrease their trust in you, and ultimately avoids one of the key reasons you’re writing it – to clarify your own thinking.

So pick one project this week and write a one-page brief before you begin execution. Don't overthink it. Just capture the goal, your approach, and how you'll measure success.

You might find, like we did, that this simple practice sharpens your thinking.

Have a great week,

Taylor

I agree with your take, Taylor.

I have always been a practitioner and promoter of this approach. Moreover, there are usually significant differences between what was said, what was written, and what was finally carried out.

Writing helps to clear minds at individual and collective levels.

From my experience, there is another important detail to consider when implementing this approach. Context.

By doing that, you build context, sequence, and stories to work with. You have a detailed timeline that is valuable for evaluating strategies and practices. Finally, it also facilitates data-driven decision making.

Under an AI-driven org, this written timeline makes AI adoption and getting value within much easier.

Glad to have you back Taylor :)