How to get rich in Silicon Valley

Why founding or joining an early-stage startup is the worst way to make big money

👋 Hi, it’s Greg and Taylor. Welcome to Personal Math, our newsletter on how to make high-stakes professional and personal decisions in your 30s.

Today, we’ll cover how to get rich in Silicon Valley. If you’re in it for the money, don’t be fooled by the allure of founding or joining an early-stage startup.

Read time: 15 minutes

In 1991, I sold my first start-up for $250K (seems quaint now) to move to the Bay Area. I was young, ambitious, with infant twins, and I wanted to chase the Silicon Valley dream: start a tech company, get rich, change the world.

It’s what attracts so many of us to start-ups – the promise that if we work hard enough, starting or joining a startup will translate to a $1 million-plus check, through acquisition or IPO. How else can you afford a down payment on a house in the Bay Area, Seattle or New York area?

And sure, this might happen for you. But it’s a tough road. I’ve done 5 start-ups, four as founder/co-founder, one as hired gun CEO. Three exits – $250K, $30M and $150M. (Though it’s not about the size of the exit, it’s about the size of your stake – and your tax treatment). Plus a wipeout, too many pivots and layoffs, and LOTS of life-shortening stress.

Once a week, I talk to someone in the second decade of their career, trying to figure out a career move that will combine impact with “fuck you” money. Many of them think that founding a company or joining an early-stage startup is the way to go.

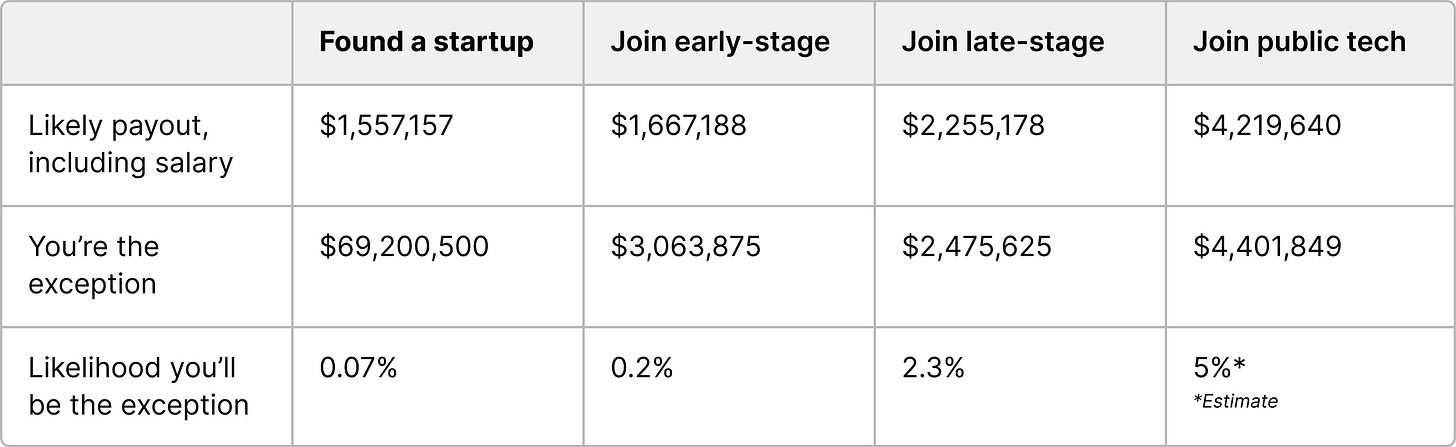

So let’s do the math. In this post, Taylor and I will break down the expected financial outcome for the four most common career moves in Silicon Valley.

Found a VC-backed startup

Join an early stage startup

Join a late stage startup

Join big tech

There are many more ways to make money in tech (venture law, VC, commercial real estate, etc.) but the options above represent the “Silicon Valley dream.”

– Greg

Option 1: Found a VC-backed startup

You’ve got an idea for a startup and some signs that customers are interested. You could be the next founder(s) of Stripe (combined net worth = $11B) … or you could be the next guy with 30 laptops for sale on Facebook Marketplace.

When most people think about founding a startup, they imagine the promise of IPO or acquisition by Big Tech. For most venture capitalists, startup success is defined as $100 million in revenue (aka “venture scale”), because it allows you to exit at a 5-6x multiple and ensures a large payout for investors and founders.

But this is incredibly rare. Between 2007 and 2017, 39,732 SaaS companies were founded, 22,096 were VC-backed, and only 288 had reached $100 million in ARR by 2022. That’s 0.7%.

If you do manage to get to $100 million in revenue, we can make a few assumptions.

You exit at a 6x multiple (the average in B2B SaaS in 2022 was 5.8x), for a valuation of $600 million

You raise $119M before exiting (the average amount raised by companies that exit)

$150M of your exit valuation is in preferred shares, or the shares that are paid back to investors before you make any money

You own 15% of the company (Note: This is the average, but it can range quite a bit. Docusign’s Thomas Gonser owned 1.5% of his business when it went public. Mark Zuckerberg owned 28%.)

If you founded this company and it hit $100 million in revenue and exited with the median ownership stake, you’d make $68 million.

But the chance this actually happens is incredibly small.

As we mentioned above, only 0.7% of startups get to $100 million in revenue, and only 9% that raise a seed round exit. The vast majority burn out before raising a Series B.

The average founder might make $68 million when a company succeeds … but the chances of this happening are 0.07%.

Put another way, if you discount your $68 million outcome by the chance it happens, your outcome would be $44,157.

Add in the average startup founder salary, and your likely earnings would be $1.6M over the 9 years it takes to exit.

You might still choose this path if you …

✓ Only work at peak capacity when the odds of success are low

✓ Just can’t stand working for someone else (Greg’s problem)

✓ Believe so much in your idea that you have to try it (this is the best reason, and this irrational delusion is the only way to explain why so many people subject themselves to the pain of a starting a company)

Option 2: Join an early-stage startup

Your high school buddy comes to you with a pitch to join their new company, Something AI.

The math here is similar to founding a startup, but you have a different (lower) equity stake, a different (higher) likelihood of exit, and a different (higher) likelihood you’ll exit at a significant value, since you’re joining later in the journey.

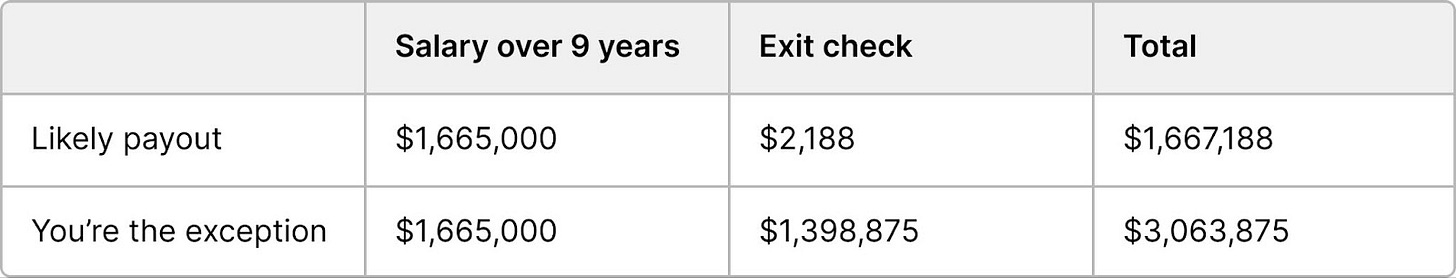

Let’s make a few more assumptions:

You’re joining a VC-backed Series A company, so they’ve already hit $1 million in revenue

This increases the odds they’ll hit $100 million in revenue to 1.3%

The median equity grant for employee 5 at a startup is 0.31%, and at this point, the company has a 12% chance of exiting.

With this equity stake, your payout at exit would be $1.4 million.

The chance this actually happens is slightly higher than founding a startup, but still quite small.

A 12% chance of exiting x 1.3% of getting to $100 million in revenue = a 0.2% chance of getting the $1.4M payout.

That’s a discounted outcome of $2,188.

Add in the median sr. director salary at a startup ($185K) over the 9 years to exit, and your expected total earnings would be $1.7M.

You might choose this path if you …

✓ Want a lot of responsibility and autonomy at an earlier stage in your career (like Taylor does)

✓ Like the energy and camaraderie that comes from building a company from the ground up

✓ Can accept some risk and instability in your personal life (e.g., you might - no will - get laid off at any point)

Option 3: Join a late-stage growth company (no longer a startup)

In this case, you have an opportunity with a company like the cloud API firm Kong, which raised its series D in 2021 and surpassed $100M in ARR this year.

A company like this has presumably found product-market fit, and is figuring out how to scale to over that $100 million threshold.

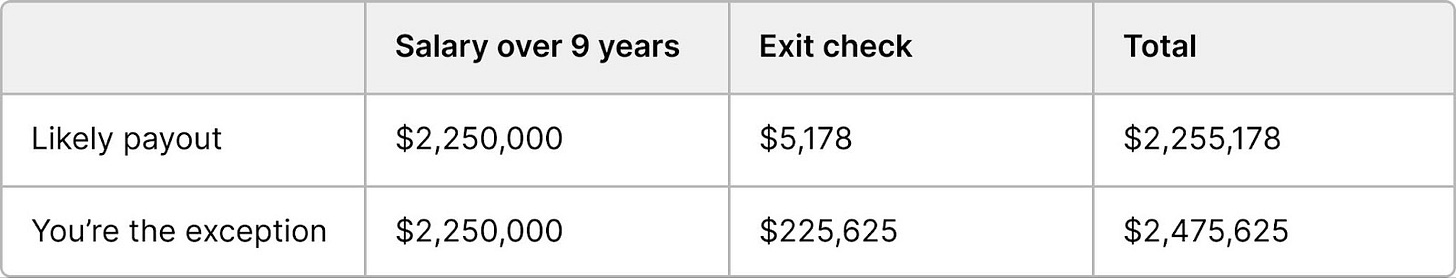

The allure here is that the company has made some traction and is more likely to exit, and at a significant value. Let’s break it down:

The company has a 16% chance of exiting, compared to 12% for an early-stage startup.

They’ve already hit $10 million in revenue, and about 14% of these companies get to $100 million in revenue.

The average equity grant of a series D company is around 0.05%

If the company gets to $100M in revenue, the average payout is $225,000 – making your discounted outcome $5,178.

The median director salary at a series D startup is $250K – let’s assume it takes 5 years to exit and you stay for another 4.

That’s a total expected earnings of $2.3M over 9 years.

There is one other consideration for late stage startups – your shares are more likely to be traded on secondary markets, increasing your odds of liquidation. So that 16% chance of exiting could be higher if you are able to sell your shares on a secondary market like EquityZen or ForgeGlobal.

You might choose this path if you …

✓ Want the culture of a startup without the instability of early-stage startup life

✓ Are impatient for IPO/acquisition and don’t want to wait years to do it

✓ Can join as a VP and get a much higher equity stake

✓ Want a more established/known logo on your resume (and an easier path to public tech)

Option 4: Join a public tech company

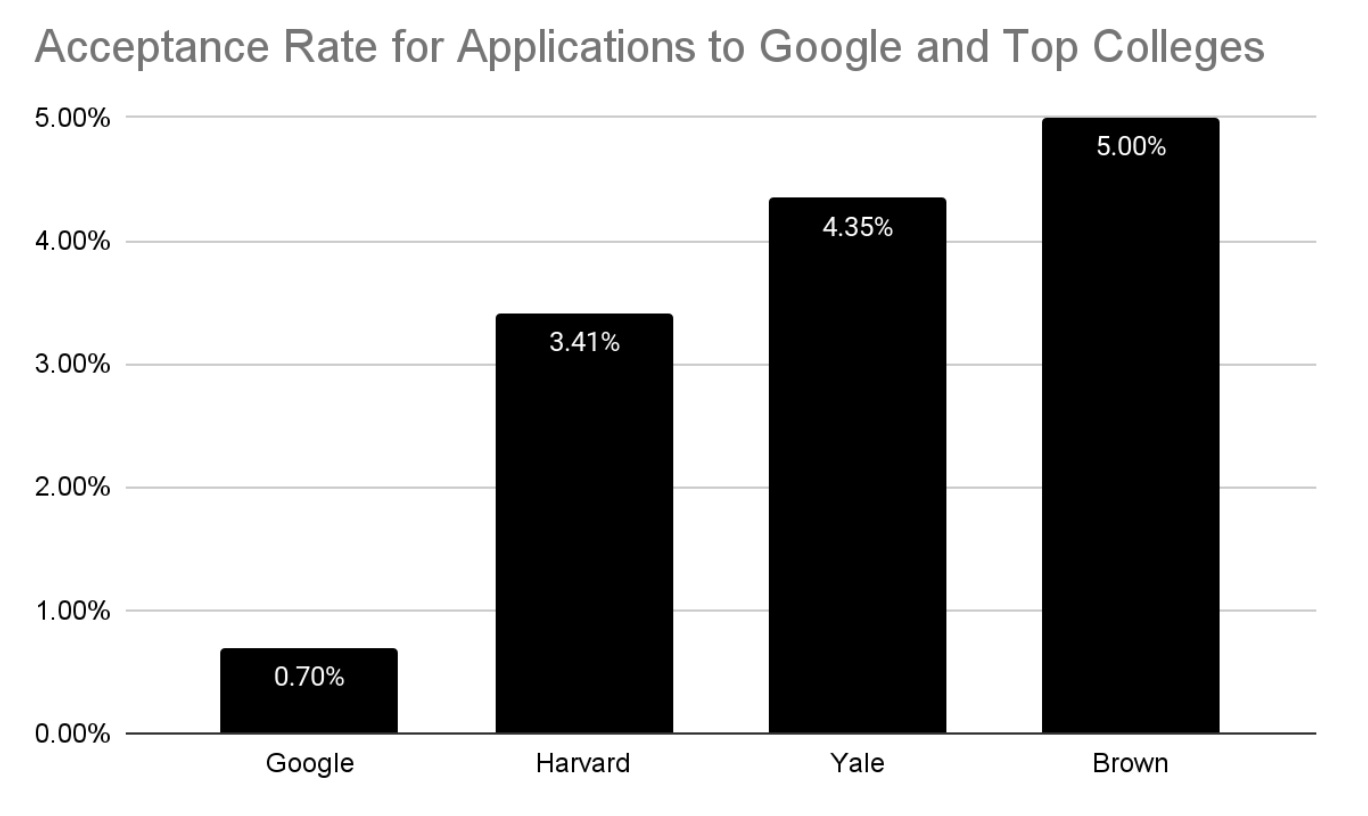

Forget startups – maybe you want to join a big, established player like Google or Snowflake. Much lower risk, more stability, and a steady (big) paycheck … if you can get the job.

The biggest challenge here is getting hired in the first place. Google’s acceptance rate is 0.7% – it’s easier to get into Harvard. Others are likely higher, but still tough – maybe 2-5% are accepted at Doordash, Instacart, or Databricks.

But let’s assume you can get the job, and you’re coming in at senior manager/director level (though tech firms like Google and Lyft are slowing down promotions as they try to flatten their org structures).

As a director, you’re making around $360,000 per year for a non-engineering role, with an average annual bonus of $16,000

You’ll also be granted RSUs (restricted stock units), at an average annual value of $80K per year

Over 9 years, those RSUs would be worth $835K, using the NASDAQ 100 Technology Sector Index as a proxy for average public tech company performance.

Total expected earnings over 9 years? $4.2 million. (Higher if you’re the exception and work at a company with a surging stock price like Google or Snowflake).

You might choose this path if you …

✓ Are a competitive applicant – these jobs pay well because they’re hard to get

✓ Want experience working in a large, complex organization

✓ Want a top-tier logo on your resume, which will make it easier to get other jobs

✓ Are a top decile performer who enjoys proving yourself against a large group of peers

Our conclusions

When you do the math, it’s obvious – joining a public tech company is the best option.

You won’t be buying an island or jet any time soon, but you’ll generate predictable wealth, if you get the job and climb the ranks.

If you want to join a startup, late stage is better – the salaries are higher and so is the exit potential. And there’s always the very small chance that you join a once-in-a-generation company that’s valued at several billion by the time your options vest (think Airbnb, Snowflake, Workday, OpenAI). In these rare cases, even a low level worker bee gets an equity stake that could convert into a down payment on a house. But assume this isn’t you.

And if you’re still thinking, “I have a great idea, and want to be a founder” or you’re itching to be employee #5?

Hey, we get it. We did it too. Our advice: Think like a venture capitalist. Know that most venture-backed early stage companies will be worthless. Evaluate your start-up honestly for its potential to exit – don’t just listen to what the founder/CEO (or the chief hype master) says.

And if that exit looks unlikely or unknown, then be honest with yourself. Work there because you love it, want a lot of personal autonomy, and/or care about the company and mission. Or move on, and place another startup bet.

To the next 10 years,

Greg & Taylor

P.S. Here’s our worksheet with calculations and sources. We’d love to hear from you. Work in public tech? How do our assumptions compare to your RSUs? Just joined a Series A startup? What was your equity stake like? We’ll share your insights in a follow up.

This is a great article and very useful. I’m in the life sciences where salaries can be lower and not all the assumptions hold. That said, your assessment of founder pros and cons and ultimate exit value were dead on for the start-up I cofounded. Rounding it out, when I joined a Big Corporate medical technology company, it was a lucrative ladder climb but I found I wanted more autonomy and had trouble thriving in a rigid org chart

Nice work, keep going.