Don’t take venture capital

The VC business model (putting a lot of money to work) is not your business model. Delay as long as possible before you raise that big round.

👋 Hi, it’s Greg and Taylor. Welcome to our newsletter on how to make high-stakes professional and personal decisions in your 30s.

My last two startups raised $60 million and $37 million – based on our ambition, availability of capital, assumption of a large market, and desire to move fast. In both cases, we raised too much.

Lots of dilution, lots of stress, and lots of late nights looking for bigger markets. It wasn’t a total loss – FirstUp sold for $150 million and hopefully will exit again in the next three years (I still have 100,000 shares). Section has capital in the bank, is growing, and is building real enterprise value.

But my lesson from both is: Delay raising lots of venture capital until you are VERY confident you have a real venture-scale business.

The VC business model (putting a lot of money to work) is not your business model. The odds that you build a venture-scale business are very, very slim. So delay taking VC as long as possible.

– Greg

The venture capital business model is not your business model

When you raise venture capital, you’re signing up to build a venture-scale business.

Lenny Rachitsky has a great post that defines venture-scale businesses – but here’s the quick rundown:

$100 million in revenue

$1 billion-plus valuation in 10 years

Fast growth (2-3x annually)

Huge market ($5 billion-plus)

Ability to unlock massive growth through an infusion of cash

VCs are looking for these businesses because it’s how their business model works.

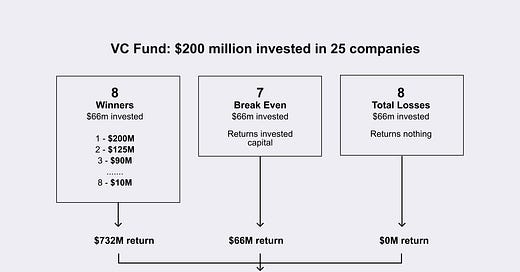

Here’s the VC thesis: Invest $200 million across 25 companies and assume that one “returns the fund,” which requires a 20x return. That one is the unicorn – it took $8-10 million from the VC and exited for billions of dollars in 10 years, returning $200 million to the VC. One Uber can return the fund even if the other 24 companies return nothing.

That’s how VCs get rich. But it’s important to understand what happens to the other 24 companies – because that’s more likely to be you.

A third are usually total losses – they return nothing to VCs or founders. A third “break even” – VCs get their money back, the founders get little or nothing. And a third get some return, which varies significantly (not every “winner” is a billion dollar exit).

Source: Elizabeth Zalman & Jerry Neumann, Founder vs. Investor, 2023.

Getting to venture scale is incredibly difficult (and unlikely)

Among SaaS companies founded between 2007 and 2017 that raised venture capital, only 18% reached $10 million in revenue.

And only 1.3% ever reached $100 million in revenue (or venture scale).

You might be that 1 in 100 company. But chances are you’re not.

Getting to venture scale is uncommon because it requires a huge market. To get to $100 million in revenue, you could capture 10% of a $1 billion market – but this is REALLY difficult. A more likely scenario is to capture 2-5% share of a $3-5 billion market.

However, way more companies raise significant venture capital than will win $3-5 billion markets. Those companies will end up being the losses, break evens, and small winners.

And the more you raise, the less likely you are to make anything back. Remember: preferred shares get paid back to investors first, so if those shares are greater or equal to your exit value, you won’t make anything.

You don’t need venture capital to build a valuable business

Despite the Silicon Valley hype (and All-In podcast), lots of successful companies don’t take venture capital – or delay the decision for a few years until they better understand their market.

Patagonia, Spanx, Plenty of Fish, Mailchimp, and Tough Mudder never took venture capital. SimpliSafe bootstrapped itself to $38.5 million in revenue in 8 years before raising a $57 million Series A.

Github waited five years before it took venture capital (and then raised $100 million). Shopify waited four years to raise VC money, and then raised $22 million.

You also don’t need to take venture capital to exit via acquisition.

There are entire private equity firms devoted to acquiring companies that don’t raise venture capital and don’t get to $100 million in revenue, including Constellation Software, Tiny, and Enduring Ventures.

Delay taking venture capital – because it comes with a cost

We’re not advocating to never take venture capital. Some businesses require large amounts of upfront investment to get off the ground or keep pace with competitors (e.g., many AI startups today).

But resist the temptation to take as much capital as you can get your hands on. Delay the decision as long as you can, until you have more evidence about your market size and your product-market fit.

You might be thinking, “Okay, so maybe I’m one of the 8 companies that don’t return anything to the fund. But why does that matter? Shouldn’t I just take venture capital and see what happens?”

No. Because raising venture capital before you have product-market fit in a very large market sucks:

Once you take venture capital, you need to put it to work, which often means aggressive hiring. But if you realize your market is smaller or slower than you thought, that means you have a staff that’s disproportionate to your (slower-than-expected) growth. You end up with layoffs in a year or two.

You make product and go-to-market decisions that are only sustainable with VC money (i.e., lots of capital), which sets you up for failure if your revenue growth slows down, or capital dries up.

You end up with a “resentful codependency” between founders and investors. Investors resent having to show up to board meetings, because they’re not seeing a venture scale business. And the founders can’t see an exit either, but they stick around waiting for one because of the work they’ve put in. (LOTS of companies from the 2020-2021 vintage are in this position right now.)

Worst – you pass up or pivot out of good, smaller markets because you’re constantly looking for the huge one.

This last one is important, because even though venture capitalists can’t get significant returns from non-venture scale companies, you can. Here are two scenarios.

Scenario 1: You start a VC-backed company

Let’s assume you take the traditional VC route – raising millions of dollars across multiple funding rounds. You get to venture scale – $100 million in revenue. If that’s true, we can make these assumptions:

You sell the company at a $1 billion valuation (10x multiple)

You own 15% of the company (median founder ownership stake)

It takes you 9 years to exit (avg. exit timeline)

You’ve raised $119M (the average for startups that exit), which results in about $150M of preferred shares (which gets paid back first before any shareholders)

In this scenario, you’d own 15% of about $850 million of common shares, making you $128 million.

But the likelihood you get here is low. As we mentioned above, only 1.3% of VC-backed companies get to $100 million in revenue. And about 15% of late stage companies exit via acquisition or IPO. So your chances of making $128 million are about 0.20%.

Scenario 2: You bootstrap the same company

You don’t raise venture capital – instead you test your product on Kickstarter to start, then you raise a smaller round with angel investors, and maybe add some debt.

You get $10 million in revenue in 10 years (it takes you longer with less capital) and you sell to an acquirer. Then we can make these assumptions:

You own 50% of the company, with the rest co-owned by angel investors, co-founders, friends and family, employees, and maybe the bank

You sell the company at a significantly lower multiple (2.5x revenue) for $25 million

At 50% ownership, you’d make $12.5 million.

This is still uncommon. Only 10% of all SaaS companies (with or without VC) get to $10 million in revenue. And 0.05% of firms that don’t take VC get acquired or IPO. But, this varies greatly by firm – among top performing non-venture backed firms (which at $10 million in revenue, yours would be) the acquisition rate is more like 3.8%.

So your chances of making $12.5 million are 0.38%, or 2x the chances of your return in Scenario 1. We’d take a higher chance at $12.5 million – that’s still life changing money for most people.

Our advice

Our advice to founders: Delay the decision to raise venture capital as long as you can. Until it hurts.

Raise from customers, angels or friends and family. Can you get your first 10 paying customers with $100K or less of capital? 100 paying customers with less than $500K?

Get into YC or a similar incubator. But when you leave that program, take a hard look in the mirror. Do you have any evidence of a venture-scale business? Even if you are hot, with lots of investor interest, temper expectations and the amount of capital you raise until you see more evidence of product-market fit.

Start conversations with investors – but keep them warm while you continue to validate your product market fit. Or find venture capitalists that are okay with a slower approach (they are hard, but not impossible to find – check out Calm Company Fund).

Be open to smaller markets that can still support a $5M+ business. You should be able to generate a decent salary, some EBITDA and also keep the option to sell the business in the future.

You may eventually decide you want to take venture capital and go for the big swing, but do so eyes open. Don’t play the VC game unless you think you are operating in a very large market.

Venture capitalists want you to take the money and go fast. Even now, in the post-ZIRP era, when venture capital is harder to get, funds are still big and partners want to place big bets. Ignore their math. Focus on your math.

Remember, a $3-$5M exit would be meaningless to most VCs. It’s probably life-changing for you.

To the next 10 years,

Greg & Taylor

Great advice!

These essays are gold. Highly appreciated, I read every word of every one. Thanks Greg and Taylor.